Celebrities Behind Bars! A Comprehensive Study of Bad Behavior and Forgiveness

by O. C. Ugwu

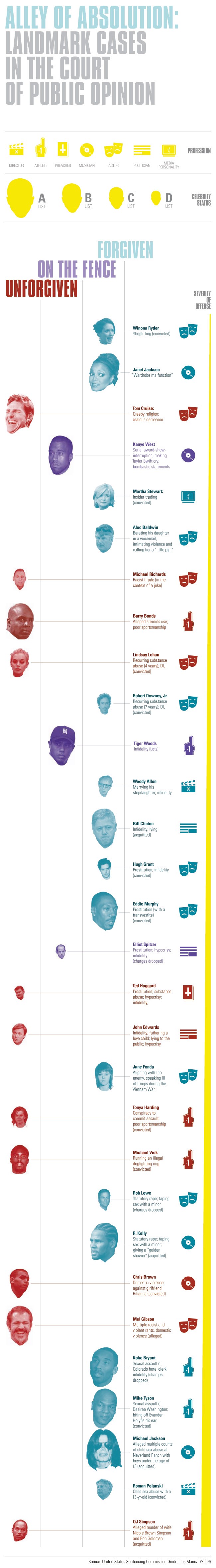

As reliable as March Madness or a fall fashion issue, every year the American public is rocked in its mores by several extremely high-profile displays of bad behavior on the part of our own faithfully erected idols. When one of these events occurs-say, the dramatic exposure of Janet Jackson’s nipple during the most watched television event of the year, or the release of blood-curdling phone conversations with Mel Gibson-there are always two competing impulses: outrage and tolerance. Over time, as both the celebrity and the public go on about their lives (and the publicists go on about their damage control) and the full nature and context of the mishap settles in, one of these impulses wins out over the other. Either tolerance creeps in (“It’s just a nipple”) or the stubborn embers of disgust refuse to die out (“He’s a monster!”).

This summer, as I watched Chris Brown stage tears during no less than a tribute to Michael Jackson at the BET Awards, and sat by the computer screen as Lindsay Lohan prepared to go to prison yet again, I thought that there must be some sense to all of this.

In the court of public opinion, Michael Jackson is widely judged to have been a curiously sexed child molester, yet the outpouring of love for him even during his trials and after death seems virtually unrivaled by that of any other public figure. If there is some criterion for surviving your crimes while in the public eye, young Brown and Lohan simply must not have met it.

By taking a closer look at the recent history of celebrity scandals and the public reaction to them, we can gain some insight into what behaviors Americans consider tolerable and from whom. Working with my friend and colleague, the graphic designer Matthew Goodrich, I set out to map this fertile terrain as clearly and definitively as possible.

The Process

Instances of public figures behaving badly are legion. (What would any celebrity be without the “Controversy” section of his or her Wikipedia page?) I settled on a diverse set of 30 of the biggest offenses and offenders, dating back to Jane Fonda in 1972. I then began to break down the dimensions of each scandal by observing whether the offender had been “forgiven,” “unforgiven” or left “on the fence,” while taking into account important factors like their level of celebrity status, the severity of the offense and whether or not the celebrity was convicted in an actual court of law.

Forgiveness, of course, is a relative term. In this case I looked to the free market and the press for definitive evidence. The questions used to determine the forgiveness metric were: “How has the public at large responded to the celebrity’s work (movies, albums, endorsements, etc.) after the scandal?” And, “What is the tone of current media coverage?” In some places those diverged. (Notably: Roman Polanski, who completely meets the first criteria but not the second.) Those deemed “on the fence” often committed their offenses too recently, or have not yet produced enough work to be sufficiently judged.

For level of celebrity status, I considered achievements in the offender’s field (Platinum albums, Grammys; blockbuster films, Academy Awards; Championship rings, world records; level of public office held, and so on) and general name recognition. Celebrities were ranked on a 4-point scale ranging from A-List to D-List. (It is important to note that celebrity status does not refer to present status, but status at the time of the offense. Often infamy increased a celebrity’s status.)

Severity of offense is tricky to measure. But, as in every case, I sought some level of objective standard. For ranking each offense, the questions asked were: “What do our laws have to say about this?” And “How uncomfortable would the average person be if they knew someone who had committed this offense lived next door to them?” For those whose offense is a recognized federal crime, placement on the spectrum was influenced by the severity of punishment recommended by the United States government in the United States Sentencing Commission Guidelines of 2009.

Conclusions

The old saying goes, “To err is human; to forgive, divine.” But even faced with moral crises as messy and mercurial as R. Kelly’s laundry, people seem to reserve a unique capacity for forgiving the famous. Of the 30 celebrity offenders considered, 19 were “forgiven” or “on the fence” while only 11 remained “Unforgiven.”

Though jurors on the court of public opinion are inconsistent (good ol’ Tom Cruise can’t get a break), examining the graphical representation of the data makes certain trends clear.

• Charges of violence (against people or animals) are more devastating than charges of sexual impropriety, for example.

• Certain offenses, though not actually criminal, are particularly lethal for the reputation (racism, hypocrisy).

• And women got off more frequently than men (2/3 forgiven, compared to 1/2). (That may have to do with the fact that no women were accused of dogfighting or hiring prostitutes.)

• The biggest factor determining whether an offender was re-embraced by the public, however, was celebrity status. The bigger they are, the softer they fall. The “Forgiven” column is dominated by A-Listers, suggesting that public figures can insure against almost any indiscretion by winning over a quorum of hearts and minds beforehand.

Perhaps the wise cultural arbiter Dave Chapelle put it best, in making the case for Michael Jackson: “He made Thriller! Thriller.”

O. C. Ugwu is a writer with one and a half credits in statistics. He lives in Brooklyn.

Matthew Goodrich is an excellent graphic designer, who has better things to do. He also lives in Brooklyn.