When "White Folks' Bay High School" Did 'The Wiz'

by Dan Kois

When the choir director, Mr. Swiggum, announced that the spring musical my senior year at Whitefish Bay High School would be The Wiz, it seemed an absurd choice. Our northern Milwaukee suburb was already colloquially known as “White Folks’ Bay,” and the preceding year had not done much to improve the community’s image in a city that studies have suggested is America’s most segregated.

In January of that year, a freshman student, the son of a prominent local attorney, got a ride home from practice from his basketball coach. Their car was stopped by Whitefish Bay police in front of the student’s house, and the coach was allegedly thrown to the ground and kicked-for no other reason, many of us at the high school assumed, than that he was black. A civil suit against the officers and the village was dismissed three years later, but whatever actually happened that day, the incident reinforced a broadly accepted notion that to be black in Whitefish Bay was, at best, unlikely, and potentially illegal.

The same winter, the school newspaper, the Tower Times-of which I was an editor, alongside future modesty advocate Wendy Shalit-ran an anonymous letter from a white student complaining about the school’s annual Black History assembly, describing it as exclusionary. Many of the school’s minority students-almost all of them bussed in from Milwaukee proper through the Chapter 220 program-protested. For the first time in recent memory, race was an issue everyone wanted to talk about, instead of an issue that everyone pretended not to think about. The series of consciousness-raising round-tables that followed didn’t really change anything, but were, needless to say, awfully formative for a suburban kid just beginning to embrace his liberal white guilt.

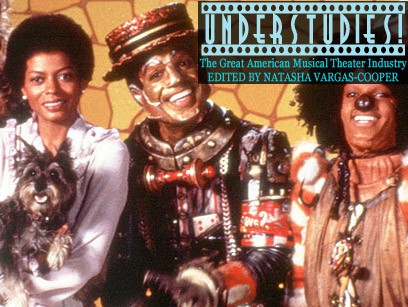

So: The Wiz. In a way, it was a canny move on Mr. Swiggum’s part-confronting our school’s lily-white image (and reality) head-on with a musical steeped in black culture. And, after the basically all-white spectacle of the previous year’s Fiddler, it wasn’t at all a bad idea to program a show that might get the school’s aspiring black performers to audition.

But at the time it seemed ridiculous, like the punchline to a joke about our school. (Setup: “What musical should never be put on at White Folks’ Bay?”) Obviously a whole bunch of the characters were going to be played by white kids. Would they embarrass themselves? Would they offend black students in the audience? Would any of the school’s black students even attend, or would they be so offended by the co-option of this show by the school’s dominant power structure that they’d, I don’t know, stage a boycott? Would the boycott get on the news? Would my college hear about it and call me on the phone and be like, “Oh, we didn’t know you went to a racist school, NEVER MIND”?

Whitefish Bay High School’s production of The Wiz was so rich with problematism as to be a Masters thesis, and so fraught with tuneful tension that it could be an episode of Glee. But all these issues were secondary to me, once rehearsals started. All I cared about was: How the fuck was I supposed to play this trumpet part?

Because I didn’t audition for The Wiz. While I was a theater nerd-my junior year I had played the lead in the centerpiece one-act of the school’s fall drama, a strident piece of anti-Gulf War 1 agitprop called Plays and Poems for Peace-I was not yet the enthusiastic karaoke-er I would become in adulthood, and was terrified of singing in front of people. So I played trumpet in the pit orchestra.

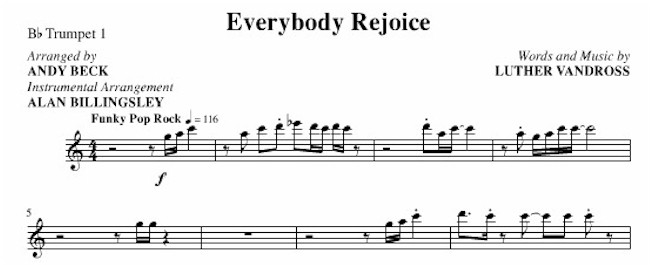

In fact, although I was second-chair trumpet in our school’s band, I played the lead trumpet parts for The Wiz, because our usual first-chair trumpet was busy playing the Cowardly Lion. And if you have never seen them before, the lead trumpet parts in The Wiz are hard.

Like, for instance, there’s a fucking E♭ above high C up there in that first line. I was just recovering from three years of embouchure-wrecking braces, so high C was a stretch. I could squeak one out now and then, not with bravado, but tentatively, like a fart in Pre-Calc. E♭ above high C? No way.

And those rhythms! The brass parts were mostly funk blasts, fat off-beat accents of 16th and 32nd notes, the kind of playing that requires not just talent but big brass balls. The kind of playing where you’re resting for eight, 15, 23 measures, and then on the off-beat of the three you’re expected to nail a note you rarely hit before you got braces.

The pit orchestra’s first rehearsal, just two weeks before Opening Night, was a disaster. Despite Mr. Swiggum’s patient conducting and positive reinforcement, we couldn’t make it through a single song. As he energetically waved his baton for “Ease on Down the Road” or “Funky Monkeys,” player after player would drop out, our faces red with exertion, until we’d all clattered to an embarrassed halt. I remember that we never got past the first page of “Tornado Ballet,” an F5 disco that rocketed along so fast that by the time I realized I’d missed a cue I’d already missed the next one.

By the end of the night I couldn’t feel my lips and I had no idea what was happening to me. It seemed like a cruel joke-that Mr. Swiggum’s insane choice of The Wiz was stripping my trumpeting of any semblance of funk or swing it once had, exposing me in all my whiteness for the world to see. I was a guy who did fine when we played “Chorale and Shaker Dance.” There was no way I could handle this.

In truth, no high-school trumpeter-black or white, funky or unfunky-could play those parts. The parts were written for Broadway players, some of the best, most versatile musicians in the world. I was no more qualified to play those lines than my fellow trumpeter was to sing “Mean Ole Lion,” or than a high-school sophomore (or, really, Diana Ross) was to play Dorothy. It was Mr. Swiggum’s genius that he didn’t care-or at least that he withheld his winces well enough to fool us into thinking he didn’t mind. He just threw us in there and did his best to guide us through, on the grounds that we’d learn more from fucking up something amazing than we would from succeeding at something easy.

In the end, we managed to hold it together for our four performances in the high school auditorium.

Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the Wizard were played by black students, one of whom would later dance with the Alvin Ailey company. My co-trumpeter, the Cowardly Lion, is now in grad school for set design at UW-Madison-where, coincidentally, Mr. Swiggum is finishing up a PhD in musicology. The witches, Glinda and Evillene, were played by pretty best friends whose good-girl/bad-girl personalities conformed precisely to the roles and who now both work in marketing. With few exceptions, I played the entire score pitched down an octave.

I only played the trumpet for two more years, and despite majoring in drama in college, have never been involved in another musical. (I got snobby about musicals, and by the time I wasn’t snobby about them anymore everyone else was much better at them than I was.) I haven’t been part of a real, scripted theatrical production (other than being the asshole who reviews it) since 2000, something that saddens me almost every day.

Eighteen years after The Wiz, the feeling of miserable failure that accompanied that first pit orchestra rehearsal is one I can call back to mind at any time. But so is the modest triumph we all felt when we finally made it through “Tornado Ballet” for the first time, during our final tech rehearsal. We didn’t crush it, we didn’t even play it particularly well, but the actors and the lights and the orchestra came together just enough to stagger to the end. Like the show itself, our run-through of “Tornado Ballet” healed no wounds and bridged no racial divide, but was not a horrible embarrassment. The silence afterward, in that auditorium empty of everyone but ourselves, was broken by the nervous laughter of a bunch of kids who couldn’t believe we just pulled that off.

Dan Kois did not care for The Revenge of Kitty Galore

.