Upper-Class Aspirants Pop Their Collars Once More

As the cable cognoscenti renews its romance with the midcentury executive class, the fashion world is observing its own long-running dalliance with a perennial 20th-century marker of privilege: the global prep complex. As Guy Trebay notes in yesterday’s Times Fashion Notebook entry in the entitlement-addled Sunday Styles section, all things prep are staging a robust comeback in international fashion-from the 30-year-later sequel to Lisa Birnbach’s irksomely iconic 1980 bestseller, “The Official Preppy Handbook,” to the successful launch of a Ralph Lauren restaurant franchise in Paris (with a menu that has to be heavy on Cape Codders and crocodile meat).

But the main preppy currency remains, of course, the look, and its coordinates remain reassuringly familiar: sunglasses, wool vests and the array of male-fashion brands that seem so unchanging as to be virtually scriptural: “Gitman Oxford cloth shirts and Sperry Top-Siders and Quoddy moccasins.” In a saner world, of course, these male preppy accessories would serve as a handy bestiary for waging a social revolution-or at the very least, treated as the half-stigmatized calling cards of predatory murderers, the way that Bruno Magli shoes and ill-fitting gloves are in Brentwood.

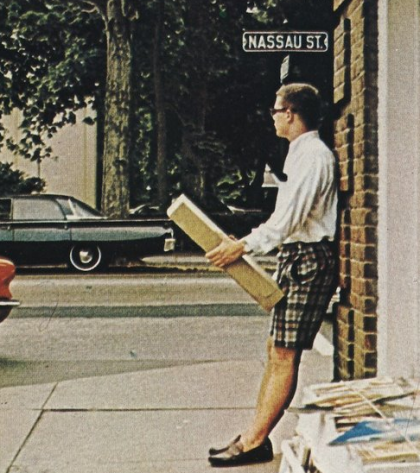

However, in the pits of fashion, the insouciant draped-sweater-and-khaki set remains cognate with the ever-dubious notion of “American classic”-an idea that becomes yet more unstable when one ponders its Japanese provenance. As Trebay notes, the allure of prep began with the 1965 publication of a photo study called “Take Ivy.” Japanese designer Kensuke Ishizu dispatched a photographer and three writers to chronicle the mid-60s WASP scion taking his leisure in the Ivied wild.

Ishizu briskly distilled the intrepid crew’s findings into his own ur-preppy fashion line, called Van Jacket (hewing faithfully to the bastardized American phrasemaking style of “Take Ivy” by again crafting a non sequitur coinage that seemed to be drenched in status-making cachet while actually saying nothing whatsoever). From there, as Trebay reports, it was on to hectic fashion renown. “Take Ivy”’s limited print run in Japan made the odd cultural document roughly as coveted among fashion arbiters as 7-inch Japanese Pavement singles had been back in the indie rock heyday. “People spent years hunting down rare copies,” Trebay writes. “They traded them online for prices that reached into the thousands. They photocopied and distributed them in design studios like fashion samizdat”-only, you know, without the general strikes and troubling popular revolts that actual samizdat tended to promote.

Retailer turned designer Michael Bastian, likewise never at a loss for bombastic overstatement, characterizes the photo source as “more influential as a myth or Holy Grail that no one could their hands on” than as an actual reference tool. When Bastian broke into the business as a Ralph Lauren assistant, he recalls, his boss “was one of those people who passed ‘Take Ivy’ around in back alleys for a long time.”

But for all this rudderless fetishizing, “Take Ivy” seems to have served as a rather wan blueprint for fashion innovation in Japan, where designers adopted it as something other than a myth and a Grail. As Times fashion David Colman noted in a remarkably similar dispatch last summer

, “Ishizu was a kind of Ralph Lauren avant la letter”-churning out chinos and topsiders at the same time that the Japanese market for youth garb was made for Levi’s jeans and Red Wing books. As Trebay writes, the hotly coveted preppy look book-which is finally being issued stateside in a 45th anniversary edition by powerHouse Books-showcases shot after shot of “handsome young Ivy League men in slim-fitting flat-front khakis, madras Bermuda shorts, anoraks, blue button-down Oxford cloth shirts and… well, essentially all the stuff you’d see in a current J. Crew catalogue.”

Which makes the insatiable interest in the damn thing all that greater a mystery for the ages-to say nothing, of course, of the broader, never-ending preppy revival that “Take Ivy” has sparked since its first appearance. Trebay makes a half-hearted effort to account for the enduring appeal of this enormously influential yet content-challenged offering. “Is it just nostalgia? Is it the vision of a bygone world populated by young men who, as the writer Malcolm Gladwell once noted, were sometimes selected by admissions officers as much as on the basis of patrician beauty as an elevated I.Q.? Is it the fantasy of upper-class belonging, the one Ralph Lauren has parlayed into a multibillion-dollar empire?”

Well, not that last thing, it turns out-since social class can never determine any feature of American life, even one so self-evidently hegemonic as preppiness. “The preppy look now signifies little in terms of class,” Trebay concludes with palpable relief. “Everybody’s a preppy when all it takes to achieve the appearance of having descended from generations of Groton men is a flipped collar, a pair of Top-Siders and checkered shorts.” It’s mere coincidence, of course, that graduates of Princeton and Dartmouth-the clubbiest and preppiest schools going in the Northeast, both overstuffed with Groton punks-top the list of salaries earned by graduates of liberal-arts institutions, according to the most recent survey findings of PayScale.com. But a far better thing to suggest that the American class system is an empty conceit than to note that the fashion system might be.

After all, wouldn’t you rather our social hierarchies be felled in an instant by a upturned collar and a carefully chosen pair of shorts than to think that maybe, just maybe, the continual rediscovery of a rakish patrician “look” betrays a telling lack of imagination in an industry predicated on the continual marketing of fake novelty? That’s just not the sort of notion that Ralph Lauren would be caught dead trading in a back alley.

Chris Lehmann is wearing socks under his shoes.