Understudies! How 'Spring Awakening' Changed the Business of Musical Theater

by Jaime Green

Spring Awakening was first produced off-Broadway at the Atlantic Theatre Company, an institution that has built its reputation on the in-your-face masculine hyperrealism of Mamet and Shepherd and McDonagh. It featured music by somewhat disappeared (but actually really good!) pop singer-songwriter Duncan Sheik, and words by playwright Stephen Sater.

The musical transferred to Broadway and was the runaway hit-also the critical and artistic darling-of the 2006 season. It is based on Wedekind’s expressionist play of the same (depending on the translator) name. In both tellings, sex is a mystery, a sin, and, eventually a killer. The fault lies not with the promiscuous youths, though, but rather the evils of a sexually repressive and socially rigid society. Wendela [spoiler alert] dies from a back-alley abortion not because she had premarital sex, but because none of the grownups in her life told her what could happen if she did. Moritz kills himself because he does not fit the narrow path that was proscribed for his life.

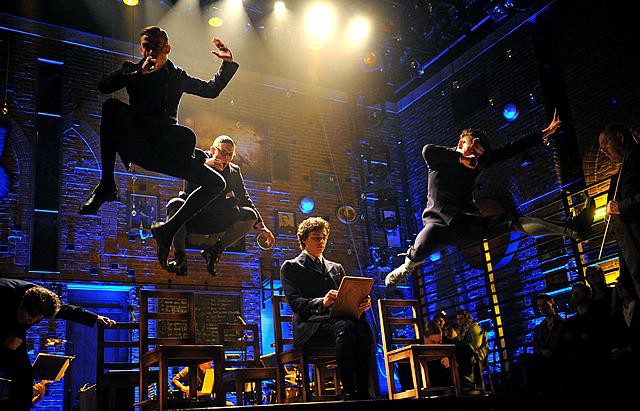

Christine Jones’ abstraction of a set colonized the entire theater with a flea market collage of old-timey paintings and objects-stern elders, idyllic seascapes, mirrors and artifacts. Lighting designer Kevin Adams bracketed tubes of primary color neon light to the walls of the space, shooting from the stage into the audience like a starburst. The stage was hemmed in on both sides by rows of audience seating, in the midst of which the actors sat between their scenes. There were also the songs sung rockstar style into handheld microphones.

Oh ho, you are saying. That sounds like some classic Brechtian alienation! Wherein the audience is reminded of the artificiality of the theater such that they can better analyze its lessons and ideas without the distractions of empathetic sentimentality! I am onto this!

Not quite.

What that on-stage seating was doing, what the microphones were doing, what all of the un-realism of the production did, was support Spring Awakening’s most daring and subtle deviation from the glorious history of musical theater. They said, “Don’t worry. We’re not trying to be realistic. Or even a realistic world where people burst into song. See? There’s no realistic set. There’s an audience on stage. Don’t worry if things get a little weird.” If it was any sort of alienation effect at work, it was subliminal: signals that you could let your realism detector rest for a couple of hours. Because these fin de siècle German schoolkids were about to reach for their microphones and sing you some rock music about their feelings.

Theatre raises storytelling to a level of artificiality by performing it for an audience, by pretending. Musicals take that artificiality up a notch by introducing the bursting-into of song. Lyrics make song more artificial by rhyming, as natural speech rarely does. One could argue that brilliant lyricists like Stephen Sondheim make musicals more powerfully musical by further heightening the lyrical language-full of clever wordplays, metaphors, and rhymes, it acquires a greater distance from natural speech. It becomes less mundane, more artful. It becomes less a conduit for factual data, and more a conduit for emotion. The lyrics start to hold more meaning than they do as individual words.

Spring Awakening goes one step further: the musical sublimates its characters’ sung words into pure expressionism. Its songs exist in a timeless space of expression. (Even when they are not non-literal they are divorced from the literal scenes they live with in — characters sing about stereos, khakis, gym class.) And so the characters are singing an inner state rather than a scene. And so song no longer advances plot. The words become a conveyance for feeling. A melody’s individual notes don’t matter — an A or a C#, whatever. It’s how they make you feel, a transmission of meaning and emotion that transcends a codified language. The songs of Spring Awakening are the closest we have gotten to such transcendence in musical theater, at least on Broadway, at least in terms of something that didn’t violently crash and burn.

* * *

On the surface, Spring Awakening felt new and different because it was a sexy rock musical about attractive young people struggling under an oppressive society. It was dark and contemporary, with an edgy (for theater) almost steampunkily anachronistic aesthetic. The songs did not sound like musical theater. They were mournful and exuberant, and there was a rock cello in the band (provided by, I have since realized, the tour cellist of New Pornographers). It didn’t look like a regular musical, and it didn’t sound like a regular musical. There was cursing and fucking and probably the most poetic lyrics ever sung about jerking off.

The character singing about the existential dread of atheism is Melchior Gabor, whose rebelliousness verges on the anarchistic. Melchior’s best friend is Moritz, as terrified and alienated as Melchior is cocky and autodidactic. He is the one who sings, agonized, about wanting to jerk off, the beauty and magic and terror of it all. He later panics and flees when Melchior tries to help him by sharing what he’s ferreted out about the mechanics of sexual intercourse. There is also Wendela, who begs her mother to tell her how babies are actually made. The young women of Spring Awakening are full of the same angsty sexual frustration as their male counterparts, if a bit more dreamily so. Wendela and Melchior rekindle their lapsed childhood friendship under the new terms of impending adulthood. At the end of Act I they have sex in a hayloft (it’s worth noting that the musical turns the source play’s rape into an act of persuaded consent)

It is also worth noting that as Melchior climbs into the hayloft, what we see on stage is this: four ropes lower to the stage, which actors affix to the corners of a large square, in the middle of which Melchior stands. The ropes hoist this platform upwards as dozens of bare blue lightbulbs slowly descend from the space above the stage, so that Melchior rises into the lights.

It is one of the most beautiful and evocative moments of theater I’ve ever experienced. I don’t even think I knew it was about climbing into a hayloft. It was the translation of a feeling into stage magic-people and objects and light in real space-and into words. There is no switch, there is no angel, no one has blinds. But those boys sing those words, and you know what they mean.

To return to the plot and our doomed young people: Moritz runs away from home and from the unbearable pressure of unreachable academic success. One of the chorus girls sings about abuse and incest. One of the boys masturbates to a sexy postcard. And there is the business in the hayloft, as the chorus sings, over and over, in rising harmonies: “I believe, I believe, there is love in heaven. I believe, I believe, all will be forgiven.”

In Act II, Moritz kills himself; Melchior sings the saddest song ever about love and regret to (but not really to) Moritz’s silently weeping father . Two boys reprise Melchior and Wendela’s love theme. Wendela is pregnant. Melchior gets sent away. He (and the ensemble) sing a song called “Totally Fucked.” Wendela’s mother takes her for an abortion. You can guess how well that goes. Melchior runs away, back to home, to find Wendela’s fresh grave next to Moritz’s. Their two ghosts come and sing with him: “Those you’ve known and lost still walk behind you,” and he decides (break from the source material!) not to kill himself, but to keep them in his heart, etc. etc. The show ends with an abstract coda of hope, sung by the entire company, called “Song of Purple Summer.”

So no, there isn’t any tapdancing.

* * *

The legacy of the superficial newness of Spring Awakening-the sexy, emotive rock score; the stylish anachronism; the extra-theatrical composer-is already being felt. Green Day’s musical, American Idiot, shares Spring Awakening’s director, Michael Mayer, and one of its stars-John Gallagher, Jr., who was nominated for his inspiredly tortured star-making performance as Moritz.

There is also Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, transferring to Broadway from the Public Theater next year. It adopts Spring Awakening’s style from the cast of sexy young people and emo anachronism all the way down (or up) to the bars of neon light extending over the audience (which Kevin Adams wryly noted in his recent Tony Award acceptance speech, which was very awesome of him).

Whether and how Spring Awakening’s more subtle innovations in the musical form will be practiced and developed in future projects and by younger writers-this is yet to be seen, although there was not long ago a workshop of a play with original music of The Sorrows of Young Werther. (Spring Awakening was in development for seven years before it was produced, so we’re talking about a slower, longer timeframe.) Spring Awakening proved that a musical can work with non-narrative songs, and can work powerfully at that.

A pessimist could see this opening the door for a bunch of crappy jukebox musicals, but that door was long ago trampled down, and this is not about winding a plot around known commodity songs. What Spring Awakening will hopefully inspire is lyricists exploring how songs can function as more than-other than-sung scenes, but can open, as music does, tonal and intuitive windows into their characters’ hearts. Musical theater lyrics can function expressionistically, rather than always literally. You know, the way pop songs do. We lament musical theater’s estrangement from popular music, but if there is a chance for musical theater to grow as a form by singing in a pop idiom, it’s not just loud guitars. It’s this.

Spring Awakening can surely attribute at least some of its invigoration of a moribund form to the fact that while its book-writer and director were theater people, its composer and choreographer were not. Duncan Sheik kicked off a trend of indie-style songwriters trying their hand at the form-Colin Meloy, Stephin Merritt, and Regina Spektor are, or have been, repped by Sheik’s own agent and at work on various theater projects. I hope that more dance-world choreographers like Spring Awakening’s Bill T. Jones will bring their breaths of fresh air to the form as well. (Jones’ strange and abstract choreography was just as daring as Sater’s lyrics.)

I also cannot downplay the importance of a show succeeding by appealing to a young audience. Spring Awakening did. On the whole, theater’s audience is old and aging quickly. So much in New York caters to elderly ticket buyers, which inspires exactly as much innovation as you would imagine. If younger people are driving sales, then producers will have to be in touch with what younger people want, perhaps our only hope to break theater out of its dismal calcification.

But they probably said the same thing after Rent.

Jaime Green would also like to mention the dramaturgical elegance of Bat Boy: The Musical. She is not kidding.