Shawne Williams and the Redemption of the NBA Summer League

There are plenty of reasons to dislike the decision that LeBron James announced last night, which you of course already know was to leave bleak, broken Cleveland for steroidal, coke-optimistic Miami. These reasons are so familiar and obvious-and the spectacle of James spending an hour of prime time television breaking up with his hometown and referring to himself in the third person so spectacularly sorry-that I’m going to skip over all that. (Although you can click here if you want to read all the good reasons James shouldn’t have gone to Miami in one place.) The whole dubious story has been covered to death, but one notable aspect of L’Affaire L’Bron has been less remarked upon. And that is that, with three players earning near-maximum contracts and the rest of the almost entirely TBD roster comprised of the NBA’s minimum wage workers, the Miami Heat have become something like the NBA’s answer to Wal-Mart. There’s a whole other essay to write about the whys and hows of the resulting loathsomeness, but I’m happy not to write it. With the LeBron Thing blessedly over, I can now go back to caring about what I, and some of your more hardcore basketball dorks, cared about all along. That would be the NBA’s Summer League, the ragged annual tryout circuit in which the itinerant power forwards and off-brand guards who will fill out Miami’s (and other teams’) benches are currently trying to get themselves noticed. It is great, and it is also kind of sad in some ways, and it is happening right now.

So because I would love to be done with the squirm-inducing synergistic fuckery of LeBron’s hour-long press conference, and in part because these peripheral guys are more interesting than anyone whose nickname is “King,” let’s talk about the NBA’s working class strivers (note: not really working class) for a minute.

One longshot in particular came to mind as I made my way through the Summer League rosters. That’s Shawne Williams, a recently indicted former first round pick who averaged 5.5 points per game for Charlotte’s entry in the Orlando Summer League. If you’ll pardon the flashback, here’s how I know him.

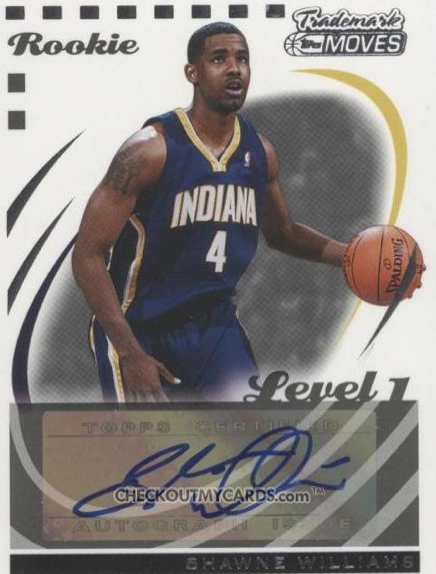

I was a couple weeks shy of being laid off by Topps when I drove to White Plains, New York back in July of 2006 for the NBA Rookie Shoot. That means that I was still the back content editor for the trading card company, and I was there to conduct brief interviews with the rising NBA rookies in attendance. For their part, the rookies were there to get their photos taken for their first basketball cards. Lost in a management-mandated extra-large polo shirt emblazoned with the Topps logo-the inappropriate sizing was presumably designed to ensure that no one confused me with LaMarcus Aldridge or other draftees-I spent the day wandering around, shagging rebounds for a few players and conducting short, rote interviews of the type that would yield trading card-appropriate information. Shawne Williams was, like every other player I met at that event-with the exception of Tyrus Thomas (so immature as to be nervous-making) and Jordan Farmar (so cocky as to actually be a cock)-seemingly a nice enough kid. Williams wasn’t as self-possessed as your Dee Browns or Shelden Williams’ or Randy Foyes-by the way, what a freaking terrible draft-but I remember him being likable, if seemingly a little shell-shocked by the admittedly shell-shocky ordeal of being photographed a few thousand times and then being quizzed by a 160-pound person in a 260-pound person’s shirt about the experience.

Williams, at the time of our brief conversation, was 20 years old, and the Indiana Pacers had just made him the 17th player chosen in the 2006 NBA Draft. In so doing, they also made him a millionaire. Given that Williams never made much of an impact in the NBA-and double-given that he was indicted for his part in a Memphis codeine-syrup ring back in January-that pick looks pretty bad today.

Williams’ thumbnail player biography is not impressive: he bombed out with Indiana, was jettisoned to Dallas, then saw his salary cap figure traded to New Jersey, which told him not to bother even showing up for practice. His personal police blotter is notably more memorable, although his run-ins with the law track pretty well with the sort of trouble that you’d imagine a suddenly very rich kid with very limited life skills getting into.

There are some differences-most 21-year-olds pulled over for dumb traffic violations can’t proffer their basketball card as a form of ID, and it’s hard to justify not showing up for a court date whether you’re an athletic wing player or druggy-but-once-promising starlet or anyone else. And then there’s the arrest for alleged codeine-related demi-kingpinnery. Williams was quickly indicted along with 24 others in the Memphis Police Department’s anti-sizzurp campaign, dubbed “Operation Lockdown.” Sizzurp being, as you’ve probably heard, the single biggest law-enforcement problem in Memphis.

Take all that together, and you’ve got what looks very much like a portrait of a solid gold knucklehead. As such, there’s not really much reason to be excited to see that Shawne Williams has surfaced-alongside ur-washout Darius Miles and a host of other refugees from The Island of Lost Athletic Wing Players-on the Charlotte Bobcats Bad News Bearsian NBA Summer League squad.

But I was glad to see him there all the same. Much more so than the NBA itself, the endearingly ragged and casual-unto-goofy Summer League was built for players like Shawne Williams. And while it’s hard to imagine anyone needing the Summer League more than Williams, there are dozens of players there who need it every bit as much.

* * *

Although he was inconsistent in college and invisible in the NBA, Williams has been a dazzling basketball player in his young life. He starred on the national champion Laurinburg Prep team that finished its 2004–05 season at 40–0 and ranked ahead of an Oak Hill Academy team that featured Kevin Durant and Ty Lawson (as well as unanimously loathed lady-punching ex-Syracuse guard Eric Devendorf, if that matters).

After that, Williams spent a year not really being coached by John Calipari at Memphis before being drafted into the pros. He then made unimaginably good money for not-playing in the NBA and dealing with what was presumably a non-stop death-stare from Indiana GM and basketball-legend-who-looks-like-an-old-lesbian Larry Bird. Williams’ career stats are certainly not very good, but his relative goodness as a player is hard to assay. This is because Williams has played so little high-level basketball. It’s also because we know so little about what kind of player Williams ever was or could’ve become, as well as about the various things that prevented him from getting there.

In his Memphis mug shot, Williams looks tired and heavy. He hadn’t played in a pro basketball game for over a year, but neither the harsh cop-shop lighting nor his athletic inactivity quite explains the palpable weariness in that shot. Of all the failures in that 2006 Draft-this would be a good spot to remind readers that unfortunately mustachioed Lakers bench lump Adam Morrison was the third overall pick-Williams suddenly had become the most serious and sad.

You’d have to work pretty hard to project that recognition onto Williams’ scared/sad face-I’d imagine he had more on his mind than his already dubious basketball legacy-but at some level Shawne Williams probably knew that photo was the end for him. Even before the arrest and indictment, Williams was plunging into the disdain-tinged anonymity that awaits athletic washouts.

Sports fans know what happens to Shawne Williamses once they stop being the most special people in the room-they disappear. When the athletic promise is dispelled, the narrative trail goes dead. There can be exceptions if the failure to deliver is dramatic enough-here, for instance, is what former NCAA champion and NBA lottery pick Ed O’Bannon is up to these days-but in sports, for the most part, “Where Are They Now?” is a rhetorical question. That mug shot and his hollow “I’ve really grown up a lot” quotes from a month before his arrest were to be the last we heard of Shawne Williams.

Of course, the person/player must go on living even after the greater sports fan world stops caring. He could go to jail for associating with the sort of visionaries who see a lucrative high in a bottle of Dimetapp or he could sign with a team in Europe, make a bunch of money and learn a foreign language. He could open a barbershop or restaurant or he could coach; he finds God or loses God; he looks-back-and-laughs or ferments in all that curdled narcissism. It all happens off camera, and it changes nothing.

The moral to Shawne Williams’ story is already written, regardless of how the middle chapters fill in. As a fan, the ending is yours to pick, not his: he’s a sad story or another goofball tragically unprepared for failure or a pampered kid never previously required not to be lazy or a nice enough guy surrounded by bad influences or a helpless/hapless product of a rotten environment or the exploitative amateur sports machine. Whatever works for you.

I can’t say that I’m pulling for Shawne Williams any more or less than I pull for anyone who has fucked up and must stop fucking up. I met him once for ten minutes and we talked about breakfast cereal and coach Rick Carlisle’s emphasis on defense. I have no real emotional stake in this. I have no idea what it’s like to be Shawne Williams, or what Shawne Williams is like. I can tell you that I seriously doubt Williams makes the Bobcats-he gets in trouble a lot and also got fat, and in most cases just one of those is enough to keep someone off a team’s roster. (Usually.) But his longshot presence on Charlotte’s Summer League roster is a hint at what makes the Summer League so weirdly inspiring and great. It provides a home for the NBA’s homeless and a modicum of hope for its hopeless, if only for a little while and if only through turning them loose in way-too-watchable pickup-style games. Given the fact that he seemingly never quite developed into anything but an object lesson in the weaknesses of the NBA’s Rookie Transition Program, letting Shawne Williams play this summer is probably the kindest thing the NBA can do for him.

Summer League basketball is very little like NBA basketball, but it is also very purely and very enjoyably basketball. There are coaches on the sidelines, including a notable crop of here-they-are-now ex-players looking to get in on coaching’s ground floor, but for the most part the players just play. It’s really as close to watching pro players in a playground game as most fans will ever get, and as such is generally worth the $14.95 it costs to watch the games online.

The Summer League’s ostensible purpose is to evaluate talent, and despite the fact that its games bear little resemblance to actual NBA games, it kind of works. Summer League players do get jobs off their Summer League showings, although those jobs are more frequently in Italy or Greece or Spain than in Indianapolis or Phoenix or Oklahoma City. (Note: in the backwards cosmology of pro basketball, the latter are the preferable destinations) Basketball-wise, it’s a place where a guy like Shawne Williams might actually look good, and maybe actually have some fun.

So, in that sense, the Summer League celebrates talent more than it evaluates it, and including players like Shawne Williams and Darius Miles and Ndudi Ebi once they’re well past their athletic sell-by dates is a part of that. No team is putting Ndudi Ebi-a turbo-bomb whose poignantly brief NBA career makes a strong case for the rule that forbids players to enter the NBA Draft straight from high school-on the floor in a NBA game this year, I promise. But whoever asked Ebi to join Orlando’s Summer League team evidently did want to see Ebi (who is still just 26) play in these ultra-serious pickup games. That nameless decision-maker-probably the same guy who will eventually stop returning phone calls from the agents of all these players-was thinking like a sentimental basketball fan, which means he got the spirit of the Summer League just right.

I imagine that whatever transcendence Shawne Williams once found in the game probably feels a long way away right now. That’s probably also true for Miles and Ebi and all the other hoops desaparecidos who resurfaced in this year’s Summer League. All the more reason to pull for them, then. Basketball gave Shawne Williams much more than he was able to accept, and I imagine he’ll spend much of the rest of his life thinking about that. But I hope that, in those half-empty Orlando gyms, Williams and the rest of the Summer League’s longshots can reclaim some joy in the game that changed their lives so much.

David Roth is a writer from New Jersey who lives in New York. He co-writes the Wall Street Journal’s Daily Fix, contributes to the sports blog Can’t Stop the Bleeding and has his own little website. His favorite Van Halen song is “Hot For Teacher.”