Let's Meet 'Charlie St. Cloud' Author Ben Sherwood All Over Again

by Jordan Carr

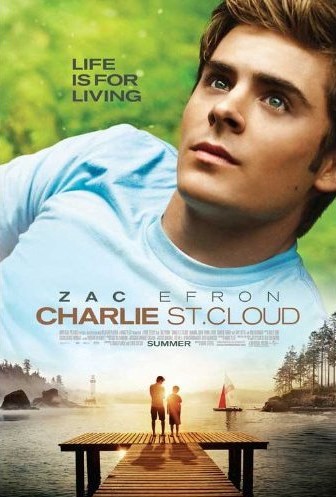

If you’ve been out and about lately, or even if you’ve stayed in-you really can’t hide from this-you’ve probably noticed a media blitzkrieg for something called Charlie St. Cloud. But before it was a movie, it was a novel. Originally titled The Death and Life of Charlie St. Cloud, any copies you find of it now will likely be of the NOW A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE variety and have Zac Efron dreamboating the hell out of the cover.

That novel’s author is Ben Sherwood. He’s not an old man-only 46 now-but his fame and controversy extends back rather far, to his days as a Rhodes Scholar.

As his Wikipedia page put it-until as recently as July 9, when it went missing, although it remains on his Facebook page-”Sherwood’s years at Oxford were so controversial that he was profiled by Andrew Sullivan in a 1989 [actually, October 1988] Spy magazine article entitled “Resume Mucho” which described him as a child of privilege deeply disliked by his classmates.”

Following in his sister Elizabeth’s footsteps, the Sherwoods became the first brother-sister tandem to win the Rhodes scholarship.

As the Los Angeles Times put it back in 1986, “The Sherwoods’ remarkable story is not one of overcoming adversity.” Their father Richard was an influential attorney in Southern California. A quick search turns up Richard E. Sherwood Awards and Internships among other things.

On the Survivors Club website, which is a follow-up to a book of Sherwood’s of the same name, he answers the question of whether or not he is a survivor rather tepidly, concluding, “while I’m not a survivor in the direct sense, I’ve been a co-survivor many times.”

Andrew Sullivan’s Spy profile (only available here!) of Sherwood, a case study of “The Young Man They Call Mister Rhodes” is embedded in a longer article about Rhodes Scholars. Sullivan pulls no punches and one gets the distinct impression we are reading about a person Sullivan didn’t like who was representing an institution he didn’t respect.

Sullivan’s story is told as how Ben’s rise to young success was as preordained as these things can be-his grooming toward a more brilliant future allegedly beginning with the Sherwoods paying older children to play with their progeny so that they might become prematurely mature. Sherwood’s precocity was noticed elsewhere-a Los Angeles Times reporter who worked with Sherwood one summer described him as “a young man going on 65.” No Pam Laffin.

Ben went to the prestigious Harvard School (now Harvard-Westlake School) in Los Angeles for high school, and earned admittance into the even prestigiouser Harvard University, where his father attended law school. From day one there, by Sullivan’s account, he did everything he could to follow in his sister’s Rhodesian footsteps and made no secret of his intentions, perhaps grating on his contemporaries. One dismayed classmate summed up the reaction to Sherwood’s cynical social climbing landing him the Rhodes Scholarship, “People were dumbfounded…not simply because he got the Rhodes but because he planned and executed getting the Rhodes. He’d devoted his life to it. When he got it, we lost all hope.”

Sullivan appears to have found it alarmingly easy to find classmates to say mean things about Ben Sherwood. One recalled: “It was a common bond among my class at Harvard, hating Ben Sherwood.” Another: “Ben is one of the most hated people alive.” Another: “It’s bizarre. People actually make an effort to dislike him.” Another: “I remember people calling one another up when he got [the Rhodes Scholarship] and saying, ‘My God! There’s no justice in the world!’” One last one: “When you think Ben Sherwood, you think funny stories, you think asshole, you think ‘Thank God I’m not him.’”

According to Sullivan, the rugby team that he joined “to lock up my Rhodes,” only to never actually play in any games, “valued his contributions so much that at their annual cookout they chose to strip him nude and funnel beer down his throat-a ritual Ben apparently took as an affectionate form of hazing.”

The Sullivan profile does not let up in its portrayal of Sherwood as the ultimate entitled, résumé-building Rhodes mediocrity (the surrounding article is about how unimpressive the “Rhodies” as a whole are-and it concludes that Bill Clinton’s speech at the 1988 Democratic National Convention just goes to show that a Rhodie will never be President). Sullivan paints Sherwood’s trip to the Thai-Cambodian border as résumé padding that allowed him take a refugee-camp sign as a souvenir to be framed and put on his wall, his decision to take a year off as ducking a strong applicant for the Rhodes from his region. Sherwood comes off as a self-important, unapologetic, pompous jerk who feigned interest in causes to appear well rounded and worked family connections into internships at the Los Angeles Times and CBS, where he added Walter Cronkite and Dan Rather to his résumé as references.

* * *

“When I came back a lot of my friends looked at me and said, ‘Ben, What was it like being in Beverly Hills after having lived at Site 7 [on the Cambodia-Thailand border] for the better part of three months?’-this sprawling, steaming camp with 55,000 people in it who have nothing, just huts and people.

I had the distinct impression they expected me to come back from this experience and reject the country club and the house and the family and the servants and the Hollywood Bowl.

I could have done that. And it would have been outrageous and it would not have accomplished very much. You don’t have to reject Beverly Hills and Hillcrest Country Club to want to care about people elsewhere.

I am very aware of how privileged I am and how luck I am and when I look at poor people, I don’t feel guilty that I have what I have.”

That’s Ben Sherwood, at 22, in the Los Angeles Times article “Beverly Hills Siblings find the Rhodes Friendly on the Way to Oxford,” Feb. 16, 1986.

The only prior lengthy article about Sherwood was this profile of him and his sister (now on the National Security Council), and that is larded with enough of Ben’s own pontifications that it makes Sullivan’s point for him. Quotes like this:

I like to think that I’m controversial because I have opinions about things and I care passionately about certain things. And I think that sometimes it is not particularly popular to care passionately about gun control or current events,” and “I’m not reluctant to make waves when sitting at a dinner table with a group of classmates when one person says something I disagree with. And Machiavelli, who is widely misunderstood, said that in the long run it’s not that important to be popular because popularity is fleeting but respect is permanent.

Fresh off his Rhodes Scholarship, Ben Sherwood went into writing, working for a litany of publications and TV shows, making a few enemies along the way, and eventually writing novels The Man Who Ate the 747 (possibly to be a movie, and, yes, a musical) and The Death and Life of Charlie St. Cloud, and more recently that non-fiction book, The Survivors Club.

Benjamin Sherwood has made his own fortune from stories that emphasize the power of personal choice to overcome the kind of obstacles he never had-stories that take place in the small, isolated communities he never lived in. Say what you will, they do strike a nerve with people and are not at all successful by accident.

Sherwood has certainly capitalized on all of his advantages with hard work. None of this proves that Sullivan’s account was right-that Sherwood is a vacuous careerist with little more to him than whatever titles and achievements he can accumulate-but it doesn’t prove him wrong either.