Vanishing Point (Your Memes Reviewed): The Joseph Ducreux Self-Portrait

In 1793, France’s revolutionary government decreed that the Louvre Palace, a much-remodeled Parisian fortress, should serve as a museum to house and exhibit the nation’s 537 greatest available works of art-mainly stuff ripped from the clutches of kings and clergy on their way out of power and up the blood-slicked steps to headlessness. Circa that same year, also in Paris, an aging portrait painter named Joseph Ducreux completed the 18th-century equivalent of a charmingly douchey Facebook profile picture, Portrait de l’artiste sous les traits d’un moqueur. The piece would later become part of the Musée du Louvre’s vaunted collection… and so much more.

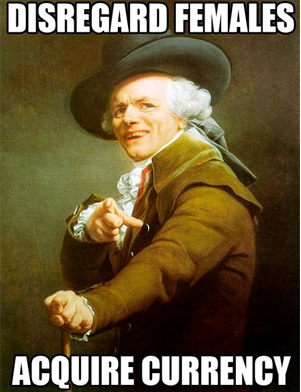

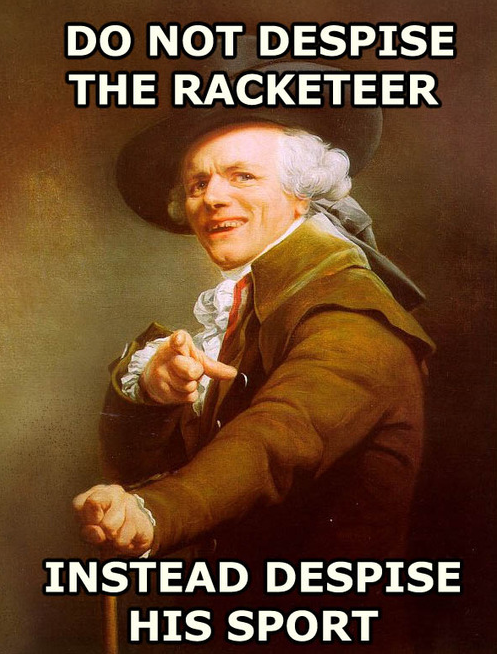

Or, well, a highly exploitable image macro onto which one might paste rap lyrics dressed up in antiquated idiom. An immediate pleasure here is the tension of anachronistic pop sentiment couched in a vernacular that struggles with those meanings and destroys the stylized phrasing of the original text. On the other hand, we instantly recognize how neatly the casual sexism and mannered delivery you might find in hip-hop fit into a historical lineage. Ducreux’s foppish accoutrements today reek of pimpage, of course, but the painting communicates with our moment on weirder wavelengths than that.

Sometimes, when approaching a subway turnstile, I take out my apartment keys instead of my MetroCard. With no conscious effort I swap one method of access for another. Then I stop there at the turnstile with my keys in my hand, wondering about what Freud would say about the fact that I seem to subconsciously regard the 53rd St.-7th Ave. subway stop as my place of residence. That the Joseph Ducreux meme works at all is a miracle on par with your keys momentarily functioning as a MetroCard, and in such a way that you never even think about the mechanism by which key and turnstile collaborated. The cultural forces in play gel simply and mysteriously, but just where do they overlap?

Helpfully, the painting breaks rules. In its mischievous artifice it echoes works painted in the wake of the High Renaissance by the likes of Raphael and Parmigianio, often loosely branded as “Mannerist.” The latter artist’s Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror is so emblematic of the first stirrings of what we’d call postmodern tendencies that archaic-postmodern poet John Ashbery borrowed the title; it flaunts its distortion and warp of a sacred medium. Despite evolving out of the classicized naturalism of the Italian Renaissance, Mannerism at its zenith held to a fiercely anti-classical philosophy and began to dissolve the correspondence between visual art and the material world it drew from.

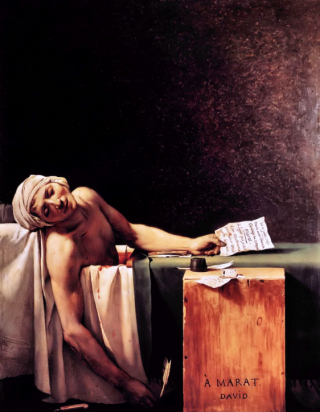

Ducreux was himself resisting a neoclassical vogue brought about by his friend Jacques-Louis David, whose pristine and humorless works became the enduring images of France’s political upheaval. The Death of Marat and The Tennis Court Oath (also a John Ashbery title, coincidentally!) are universally included in textbooks covering European history and physically idealize their revolutionary figures with a fervor that borders on sheer delusion. By breaking the fourth wall in his self-portrait-by pointing at and mocking you for the rude shock you feel when confronted by the facsimile of an ugly guy that is pointing at and mocking you-Ducreux is returning to a basic honesty about art’s deceptions and social function. The thing relishes how a viewer can interact with and construct meaning from carefully arranged pigment, and how the artist can make eye contact with his audience across impossible distances of space and time.

Meanwhile, the acute self-awareness of hip-hop, its callouts of rivals and listeners alike, its predilection for sleight of hand (or tongue?) and richly synthetic instrumentals, its realness or impoliteness, have made it the prevailing confrontational voice in art. Nothing else is at once so subversive and so stubbornly status quo. Ducreux trained as a servant to a doomed aristocracy; he drew the last portrait of Louis XVI; he was interested in physiognomy and sought persona in the shape of a subject’s skull. And yet his outmoded education primed him for a transgressive late period. Perhaps he wanted none of the formal precision and solemnity championed by David, the man who kept him relevant in a post-monarchy state, because they were just more royal constrictions on his freestyle flow. David rarely kept it real, that’s for sure. But listen, I could go on and on. Rappers make us listen hard and untangle their rhymes. The Ducreux meme happily forces some further translation.

RATINGS

(characteristics rated on a negative to positive scale of -10 to 10):

Flexibility: -0.8

Insight: 10.0

Aesthetic: 10.0

Redundancy Potential: -2.2

Confusing To Outsiders: 4.3

Final Meme Score: 21.3

Miles Klee is the planet’s only dedicated meme critic.