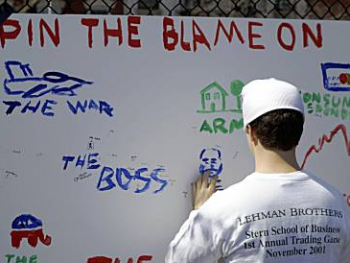

The People Who Screwed You Out of Unemployment

When it comes to the market order, there’s oversight and then there’s oversight. Just consider the evidence offered up in Sunday’s New York Times, which points up what any casualty of our job-starved economic recovery has long known: that the quotient of vigilance your particular grievance inspires depends on where you fall in the social hierarchy of the workforce. Over in the A section, Times reporter Jason DePaerle surveyed the track record of the St. Louis-based firm Talx, which a host of major US companies, from Wal-Mart to the US Postal Service, retain to contest unemployment claims filed by the cashiered class.

Talx is for some reason pronounced “talks,” though as DePaerle makes clear, the firm’s chief product is pretty much the antithesis of direct communication. Brought in to review as much as 30 percent of pending jobless requests, Talx dispatches third-party agents to mire the claims process in incomplete paperwork, absentee board-review hearings, and in some cases, outright fabrications. The tactic has become so widespread, DePaerle reports, that Iowa and Wisconsin have passed laws to crack down on Talx-style delaying tactics-while the New York Labor department now instructs its officers “to side with workers in cases that simply pit their word against those [sic] of agents for employers.”

The particulars of Talx-brokered claims disputes make a strong case for a much broader culture-wide shunning of these paperwork Pinkertons. Agents of the firm misrepresented a claims call involving Gerald Grenier, a mentally impaired Wal-Mart janitor fired for absent-mindedly neglecting to return a few dollars’ worth of change he’d pocketed from a vending machine. Wal-Mart failed to show up at a hearing the janitor got scheduled three months after his unemployment claim was denied-and a Talx agent was heard hanging up during Grenier’s testimony on a follow-up conference call hearing. Even then, the firm went on to challenge Grenier’s vindicated claim, falsely asserting that the New Hampshire Labor Department didn’t let the Talx agent testify by phone. Grenier eventually had his benefits reinstated, but not before he lost his apartment and was forced to move in with his sister.

Talx’s dilatory business model is a boon to big firms for the simple reason that the longer benefits go unpaid, employers aren’t forced to pay taxes on them. Already strapped jobless Americans are apt to just give up in the face of a full-court press from claims agents charged with making their cases as difficult as possible to process.

In one especially fragrant Massachusetts case, the company lost its challenge to benefits claimed by an employee of the epically unsound (and now bankrupt) mortgage giant Countrywide Financial when its agent failed to show at a hearing. The agent claimed that the blown appointment was due to a death in the family-a claim later recanted when probed under oath before a Salem district judge. There’s a nice origami-like structure to this entire set piece: a financial concern decimating the housing market with grotesquely unsustainable mortgage deals (indeed, the defendant, Linda Greiss, successfully alleged that Countrywide’s very business model constituted an unsafe working condition due to the attention it drew from federal investigators in 2008) hires on a claims advocate to pump the system with petty lies insulting to that agent’s own family life. And they say the spirit of American entrepreneurship is on the ropes!

The gruesome Talx track record makes for edifying reading alongside yet another mammoth Timesian breakdown, in Sunday’s business pages, of efforts to curb excessive executive compensation. True, reporter Devin Leonard notes that CEOs saw a 15 percent decline in their pay packages in 2009-largely under the pressure of Kenneth Feinberg, the Obama White House’s “compensation czar,” who approved a $500,000-a-year ceiling for the heads of companies receiving support from the Troubled Assets Relief Program.

But that decline represents an average figure, and when it comes to the way that firms go about crafting compensation plans, outliers abound. Yes, corporate boards are trimming outright cash outlays for CEOs, but those executives still rake in plenty via deferred stock plans and other sweetheart arrangements with favored corporate leaders. So that, for instance, when the CEO of Starbucks high-mindedly wrote down his salary from $1.9 million to $6,900, citing the overall sluggishness of the economy, his friends on the board shook loose a $1 million “discretionary bonus” for the company’s solid 2009 performance.

Hewlett-Packard CEO Mark V. Hurd has scored discretionary bonuses three years running-which landed him the No. 4 spot on the Aquilar annual survey on executive compensation this year with a cool $24,000,000, even though he made a show of reducing his nominal cash salary by 20 percent. Lawmakers are weighing a “say on pay” provision in pending financial reform legislation, which could permit corporate shareholders to vote each year on executive compensation plans-though it’s far from clear that such votes would be binding on corporate boards, even should the provisions clear Congress. “I think say-on-pay is pointless,” University of Delaware corporate governance professor Charles M. Elson told the Times, citing the propensity of most boards to devise workarounds that sidestep high-profile pay strictures.

Indeed, last year’s highest paid banker, John G. Stumpf of Wells Fargo Inc., came into his $19 million payday by hewing to the letter, if not the spirit, of Feinberg’s compensation plan. The California banking conglomerate received TARP funds, which it repaid in December, so it structured Stumpf’s cash payout at a comparatively modest $900,000. But the Wells board also gave him $4.7 million in annual stock issues-plus, oh, what the heck-another $13 million in stock on top of that, in part due to Wells’ TARP-orchestrated acquisition of flailing east coast banking giant Wachovia.

All of which suggests that the federal push to restructure top dog compensation could use a dose of innovative thinking. Surely there must be some reality TV franchise out there that could arrange for the Stumpfs and Hurds of the world to put in tours as night janitors at Wal-Mart. Then all you have to do is send them packing at the end of their shifts with a couple dollars in vending machine cash. It would be a vastly entertaining spectacle, as well as a slight incremental gain in cosmic justice, to see them try to get a Talx agent to return their calls.