Ciudad Juarez: Why the Press Declared a Cartel Win

by John Murray

Just a few weeks after the AP declared that the Sinaloa cartel had won the drug war in Juarez, the city saw one of its bloodiest days in recent memory. On Wednesday, 20 murders were recorded in a 24-hour span. The first murders of the day set the tone for the brutality to follow, as gunmen burst into a bar in the early morning and dragged eight people out into a nearby lot, lined them up against the wall, and executed them.

It’s something that’s become all too common, another horror story from a city where gruesome acts of violence seem to be quickly and continually supplanted by even more gruesome acts. For citizens and outsiders alike, the events themselves can tend to become indistinguishable after a while, or worse yet, almost inconsequential to the larger current of violence that had destroyed so much already. No one is ever prosecuted, and the violence just keeps on coming.

Last weekend, gunmen in SUVs swarmed two police trucks at a busy intersection and murdered six federal police officers, along with a municipal cop and a 17-year-old kid who happened to be passing by. Later in the day, a message from La Linea, the enforcement arm of the Juarez cartel, appeared scrawled on a city wall, warning that the same fate would befall all those who supported Chapo and the Sinaloa cartel. But with no real leads, and no history of people paying for these sorts of crimes, the story is already fading from the public eye.

The fact that these crimes can’t be viewed as singular events for long enough to get a hold on them before something else happens is a symbol of just how deep the culture of violence runs in the city. This larger narrative of violence that seems almost insurmountable points to the fact that Juarez isn’t merely a city with a crime problem. There is a history of impunity in Juarez that is perhaps even more sinister than the violence itself, which too often is chalked up to merely a ‘war between rival cartels,’ a definition that can be very deceptive.

Impunity in Juarez goes back a long time. In the days of Amado Carrillo, the boss of the Juarez cartel who died in 1997, unsolved murders in the city were a part of everyday life. Bodies would turn up all over the city, bound and gagged and showing signs of torture. Often they were found with a tell-tale yellow ribbon tied in bow around the victim’s head: a gift from the cartel. Few, if any, of these murders were ever solved, and most weren’t even investigated. The culprit was obvious. But he was untouchable. In addition to having most of the police on his payroll, he was Juarez’s most influential businessman at a time when the Salinas administration was bent on pushing NAFTA through. Drawing international attention to crime was far from a national priority.

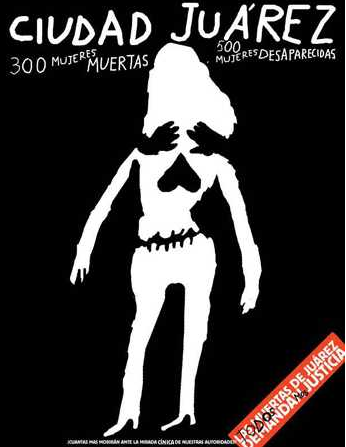

The most famous example of Juarez’s culture of impunity lies in the mass femicide of the 1990s, the peak of which coincided with the peak of Carrillo’s rule in the middle part of the decade. Over the course of the decade, roughly 400 women were found murdered in the city and another 500 were reported missing and never found. The bodies that were found were usually raped. Almost all of these crimes went unsolved. The police offered up a few suspects who went to jail, but the fact is that no one person could have been behind the murders. Most speculate, based on information that has come out over the years, that the rape and murder of women was some kind of trend among men who worked for the cartel, a way to celebrate a particular operation. Essentially, they killed for kicks. This is almost impossible to wrap your head around, but for people involved in a culture of such pervasive violence, where murder is a given, life becomes very, very cheap. When people live in that culture, with access to an endless supply of money, drugs and guns, common morals as most people understand them just don’t apply, and evil flourishes.

And this is how the children of Juarez grew up, in a city where criminal figures were the real law, and murder went unpunished.

Another big part of the city’s history was the massive influx of migrant workers during the same decade. They came to work in the US-owned maquiladoras that sprung up along the Rio Grande after the passage of NAFTA. Working for pennies a day, these migrants lived in slums that developed around the city, the perfect breeding ground for gangs, drugs and the growth of the kind of seemingly hopeless street criminal culture that pervades much of what we see happening in the city today.

This is why the situation has devolved from being a simple war between two rival cartels. Now, we can barely tell who is who. Murders have been subcontracted down to gangs of 15–25 year old kids who kill for as little as $25. These same gangs also battle each other over the growing local market for drugs. Empowered with money and guns, they’ve turned to kidnappings and extortion to make more money. Armed robberies have run rampant. In Tamaulipas, the stories we hear of the drug war revolve around trucks and SUVs emblazoned with the logo of the Gulf cartel battling against other cadres of trucks full of Zetas.

But in Juarez, the most common murder stories these days are about people who couldn’t pay extortion fees, or street food vendors being gunned down for no apparent reason in broad daylight. Not to say that those things don’t happen in Tamaulipas, but they define the situation of Juarez.

When impunity is the norm, all of the criminal elements come out of the woodwork and the situation quickly gets out of control. After Calderon ordered 7,500 Mexican army troops to be stationed in Juarez in March of 2009, things quieted down for a matter of weeks, just long enough for drug money and influence to corrupt the new guard. Then the murders started up again, and actually got worse than they were before. The Army has been accused of terrifying and intimidating the public, swept up in the same free-for-all for the huge sums of money generated by drugs as the criminal elements. The most recent step was the appointment of the Mexican federal Police as the Army’s replacement, which historically is just as corrupt as any other law enforcement group in Mexico. And that is the government’s next step in their plight to save Juarez, their ‘war on the cartels.’

This perhaps is why the Associated Press ran their story preemptively declaring the Sinaloa cartel the winner in Juarez. It’s pretty near an admission of the ineffectiveness of any other force to bring a conclusion to this systemic breakdown. It’s the outcome that everyone was waiting for, even hoping for. When Amado was clearly in charge, street crime in Juarez was almost nonexistent, at least comparatively to how it is now. This was mostly because a cartel boss has an interest in keeping it that way, as part of a well-financed agreement with governmental officials to turn a blind eye to his business involved keeping the streets clean and ‘safe.’

Ultimately though, the cessation of violence isn’t something that will change the ingrained culture of violence in Juarez overnight. Until the government of Mexico starts paying attention to and valuing the people of Juarez through social programs, better education, protection of workers and by providing some measure of public safety and confidence in improvement, nothing will change. Until people start believing that the rule of law is something that can even stand up to the rule of death and violence, that it’s something that can make a difference, nothing can be accomplished.

John Murray is a lover of obscurity. He lives and writes in Arizona.