The Black Athletes Who Don't Play Basketball

by Richard Morgan

Sometimes athletes are black. Depending on your sport of choice, this might be a big deal. And when a black athlete is on the rise-or even just in the mix-in an affluent, white-dominated sport, it becomes a very big deal. That’s because writers like to write about these unexpectedly or surprisingly black athletes. In the past decade, the term “the Tiger Woods of [sport]” became common shorthand for a certain kind of athlete: the kind who is “changing the face of the game.”

In 2005, The New York Times noted that Kyle Harrison and John Walker were both considered simultaneous Tiger Woodses of lacrosse — and that wasn’t even counting the other two black lacrosse players, John Christmas and Harry Alford, who were layered onto the story as icing.

Adolfo Cambiaso is the “Tiger Woods of polo,” according to the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel and according to Vanity Fair in May of 2009. Unfortunately, Jabarr Rosser, then a 10th grader in West Philly, was already named as a potential Tiger Woods of polo in the Philadelphia City Paper, way back in 2001.

Ai Fukuhara, born in 1988, is apparently still the Tiger Woods of table tennis, a position she laid claim to as early as 2004; she entered the sport professionally at the age of 10. But if you feel strongly that Tiger Woods should be a man, there’s also “thug table tennis” player Wally Green, also likened to the polo-and-slacks favoring Stanford graduate.

Phil Ivey is, by all accounts, the Tiger Woods of poker. Although, given that he earned $17 million in three days of playing — and another $7 million in online poker — he doesn’t need endorsement deals the way Woods does.

Kelly Slater, the part-Syrian Australian, is or is not the Tiger Woods of surfing, depending on who you ask.

Jeremy Sonnenfeld was, for a while, the Tiger Woods of bowling-due to his age, not his ethnicity. England’s Robert Fulford was the Tiger Woods of croquet, again due to his age-though he was in competition for this title with Jacques Fournier. Same with the white Englishman Phil Taylor, the Tiger Woods of darts (and, by The Independent’s measure, “Britain’s greatest living sportsman”). Although that was 2001, well before The Independent got around to writing about Lewis Hamilton, the young black Briton who is the Tiger Woods of F1 racing.

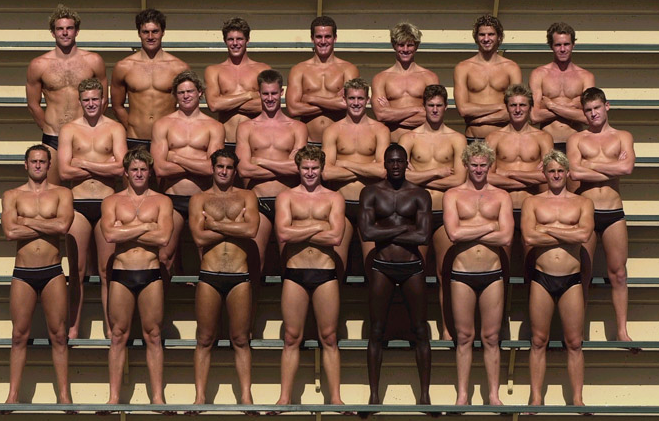

This “Tiger Woods of” system broke down some time ago-in 2001, the San Francisco Chronicle suggested that Tony Azevedo, whose coach had already called him “the Michael Jordan of water polo,” was maybe the Tiger Woods of water polo or the Bobby Fischer of water polo or the Vassily Alekseyev of water polo. Their conclusion? “Those who know water polo say Azevedo is all that — and more.”

Indeed, the Californian, who was born in Brazil, is now captain of the US National Men’s Water Polo Team. (Both his father and his sister have been professional water polo players.)

But while the “Tiger Woods of” system actually only sometimes refers to ethnicity or “difference,” the “first black in x” story hews a bit more to the specific.

Sports journalism tends to be celebratory, regardless of who is the focus of the story. With black athletes in atypical sports, stories rely on showcasing the player’s rare talent and fierce determination that have blessed him or her with the power to overcome whatever obstacles have kept blacks from joining, say, fencing teams in the past. It’s a very Billy Elliot version of The Blind Side.

But, as with The Blind Side, the story often becomes about how it takes a village of white people to transform a troubled kid by means of civilizing leisure. There’s the white adoptive family, the white coaches, the white private-school teachers, the white personal tutor. (At the same time, the idea of “leisure” is misleading. It’s also true that these are young people playing in sports with short career spans that still often destroy their bodies.) The “fuller humanity” that black film critic Armond White applauds in the movie sounds a lot like white humanity.

The stories reverberate with a sense of the impressive graciousness and broadmindedness of a sport that will let anyone play-even black people. Sure, The Blind Side is about football, which is a pretty black-friendly sport, but the premise is the same: it’s a literalization of the fantasy undergirding all those stories about black pioneers-that black progress requires the efforts of a lot of well-meaning white people.

In the Orlando Sentinel’s February, 2007 story, “Open Waters: Angler Ish Monroe is breaking through barriers in pro fishing,” it was perhaps not the best idea to describe Monroe, who grew up in Michigan and California, as “part of a new breed.” The story continues, however, with scolding recollections of Monroe being pulled over by Southern cops for driving while black. And then the well-meaning white people: Scott Laney, “a tackle manufacturer impressed enough by Monroe to front him the cash he needed to upgrade his equipment”; and Mike Iaconelli, who, in a Sports Illustrated interview, defended Monroe against claims he was “ghettoizing” fishing.

In 2003, the SF Weekly also published a profile of Ish Monroe (“Fishing the Mainstream: Ish Monroe has edge, style, and PR savvy. ESPN thinks he’s exactly what the white world of professional bass fishing needs”). Their story was included in 2003’s Best American Sports Writing and focused more on the athlete’s psychology and self-promotion, referencing his race principally but also in passing. They dealt with the issue of “flavor” (Monroe’s word) by quoting:

In fishing circles, Monroe is described as a “breath of fresh air” and “one of the hottest properties on the Bassmaster circuit” and “more flashy than a double willow blade.” Sports Illustrated says he “is changing the face of competitive fishing, a sport heretofore dominated by white Southerners.”

Sometimes, it becomes clear that everyone agrees that “black people don’t belong” in a certain sport. The forthcoming Chris Rock film is about the oh-so-hilarious concept of black skiers, who befuddle much of the world. (Gee, black people? And snow?) And in 1989, Essence ran a story on the National Brotherhood of Skiers; they marveled at “the sight of all those sisters and brothers at the summit, out there on the mountain at the crack of dawn, even after partying all night.”

But there’s a flip side to that. Peter Westbrook’s biography, Harnessing Anger, was about how he channeled his urge to fight into fencing (he now has a foundation that supports “inner city” youths in fencing programs). Harnessing Anger could be the tagline to any number of black athlete movies: Pride, Glory Road, Remember The Titans, The Express, Ali, Cool Runnings. There is Cullen Jones, “the Tiger Woods of swimming,” who grew up in troubled Irvington, NJ, and majored in English at North Carolina State University, telling NPR:

There were a lot of gangs around where I lived. The Crips and the Bloods were very big. I definitely don’t want to move back there.

So Nike gave Jones a multimillion-dollar contract so he wouldn’t have to go back to Jersey and maybe become a Blood.

Country star turned cinema actor Tim McGraw tells his Oscar™-winning wife Sandra Bullock in The Blind Side, regarding the giant financially and emotionally troubled black football player they’ve adopted: “Michael’s gift is his ability to forget.” (That comes a few scenes after Bullock’s pillowtalk observation that Michael stands out at school “like a fly in milk,” which then triggers great marital sex.) The reason this movie is popular is in part because some people do need saving. For Cullen Jones, for sure, swimming was a baptism into a brighter future.

But there can be too much amnesia. In 2003, Jet magazine wrote a story about Nigerian-Canadian Jarome Iginla, the NHL’s first black captain, by making no mention of his ethnic background other than in the headline and first sentence. After a while, one starts to lose track of why race or ethnicity is a newsworthy reason to commission a profile at all. Should we care? Which of these boundaries are actually boundaries?

And while it’s not always clear why newsmagazines treat black athletes the way they often do, there are still some boundaries that seem notable to cross.

Here’s ABC News celebrating Bill Lester becoming the first black NASCAR Cup qualifier in 20 years.

In the early ’60s, legendary driver Wendell Scott paved the road for NASCAR diversity with 495 races and one first-place finish. Willy T. Ribbs made his mark in 1986, qualifying for three events. Now, the checkered flag has been handed off to Lester. He hopes other minorities will follow his lead.

“This is an open door,” Lester said. “NASCAR’s rolled out the red carpet. It’s up to them to walk on it.”

The story ends seemingly having forgotten how it began: “Bill Lester stands out from the stereotypical NASCAR driver for many reasons: He is 45. He’s a Berkeley-educated engineer. He once held a six-figure job at Hewlett-Packard, which he left to pursue his dream.” So, NASCAR’s red carpet for black drivers has been rolled out, at least, for any six-figure-earning engineers.

Besides, Wendell Scott retired in 1973. Now, with Bill Lester being the third black person in NASCAR, that sure seems like the slowest unfurling of a red carpet imaginable.

Richard Morgan used to write op-eds for Africana.com until they found out he’s not black.