Graphic Imagery: Vodka and Fate From Russia to Brooklyn

by Dan Kois

Are you looking for an authentically grim Russian culture experience, but don’t have 12 hours and ferry fare to Governors Island to spare? A new graphic novel by Kevin Baker — the historical novelist behind such Brooklyney favorites as Dreamland — brings an ex-Russian soldier to Coney Island and gets him wrapped up with the local mob. It also calls to mind a recent, similar, much better comic, which was mostly ignored when it first came out but is finally available in collected form.

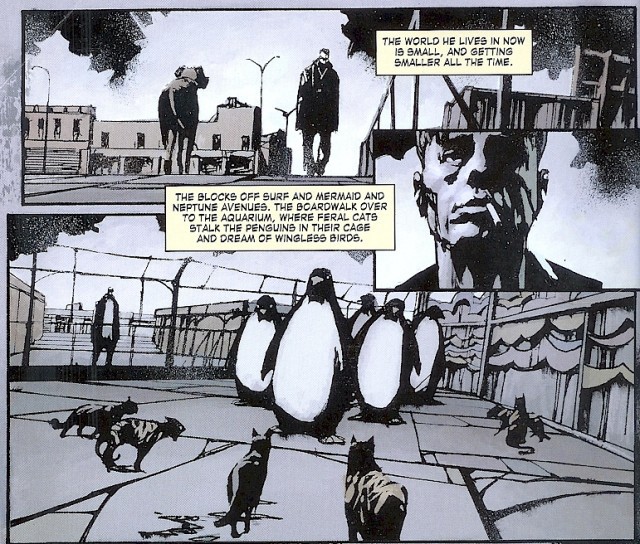

In Baker’s Luna Park, Alik — at loose ends, damaged by the disastrous war in Chechnya — winds up an enforcer for the Russian mob, and plans one final job that might get him and his lover, Marina, out of the life. It’s a time-honored plot, and Baker carries it off pretty well. And the novel’s embrace of the ghosts that haunt Russian storytelling is enthusiastic and gutsy, even if it doesn’t work all the time. It’s mostly worth recommending for the strength of Croatian-born Zezelj’s high-contrast artwork, which is so vivid and beautiful that it fills in the gaps in Baker’s story with authority.

It’s impossible to read Luna Park, though, and not remember Brett Lewis’ The Winter Men. Originally published to minuscule sales and attention by DC’s WildStorm imprint in 2005 and 2006, the series shares with Luna Park arresting, sharp-edged artwork (by John Paul Leon), a fascination with Russian history, and a hero whose psychic scars from Chechnya nearly send him over a cliff. The difference? Winter Men is grim and hilarious where Luna Park is just grim. It’s also a fantastic mystery, a gripping adventure, and — in the end — a not-unwelcome spin on the Superman story.

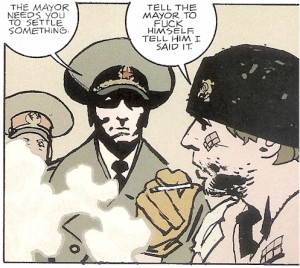

Kris Kalenov is a fixer for Moscow’s mayor, living down the ignoble end of his military career, which was spent in a secret unit called the Winter Men. When a little girl is kidnapped from an apartment by ex-Spetznaz mercenaries, Kalenov investigates, and finds his curiosity piqued by the professionalism of the job, and by the girl’s tiny handprints charred into the paint by her crib. She’s not just a kid — she’s a weapon.

What follows is part action movie, part boozy picaresque, as Kalenov — accompanied by some of his old compatriots, including Nina the assassin, Nikki the pig-fucker, and Drost the soldier — searches for the girl, and those who took her, from Brooklyn to Siberia and back to Moscow. The Winter Men also serves as an amazingly detailed look at the way a kleptocracy works, as Kalenov expertly navigates not just Mafiya meetings and back-alley knife-fights but the mayor’s office and debriefings with the CIA. He helps Nikki the gangster defend the business under his “roof,” and fights a Russian superhero that some thought imaginary.

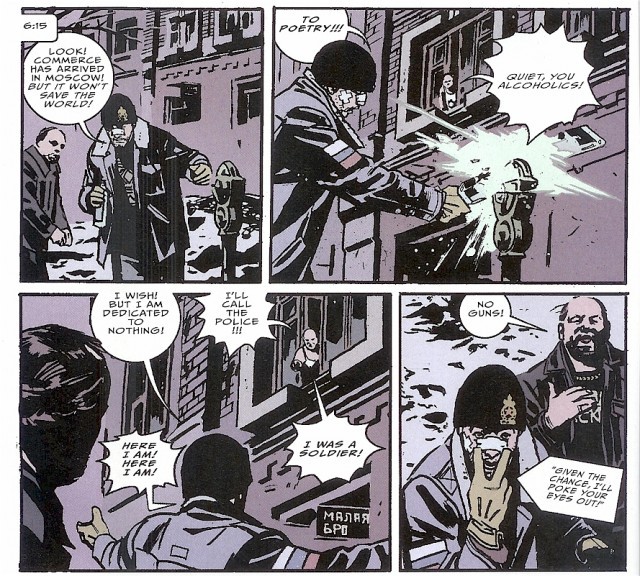

The centerpiece of the book, though, is “Citizen Soldiers,” a standalone story that barely mentions the little girl, the Winter Men, or other major plot points of the series. Instead, it follows Kalenov and Nikki through a long, vodka-soaked day as they conduct bizness, steal a table from McDonald’s for Nikki’s breakfast nook, grab a guy some lady-judge wants brought in on charges, and exchange Soviet-style wisdom, witticisms, and fisticuffs.

“Citizen Soldiers,” like all of The Winter Men, is charming and funny, and surprising, and brutal. Its ending will flat-out kill you. It is the best short story in any medium I’ve read in years. And the whole book is almost as good.

Dan Kois writes about movies and plays and non-comic books, too. Also, he has a new book out, about that Hawaiian guy with the ukulele.