Why I Did It: How I Came to Write a Comic Book About an Aborted Fetus

by Matthew Lickona

In Why I Did It, artists and authors explain just why they made something. This week, Matthew Lickona talks about the making of Alphonse: A Monster For Our Time, a comic book about, yes, an aborted fetus.

I mean, yes, what was I thinking? Here’s the rationale I wish I could give.

A lot of good horror stories are moral anxiety writ large (see also: Frankenstein and humanity’s attempt to put nature on the rack, The Bacchae as the first in a long line of what my friend Michael calls “you screw, you die” stories.) And I think it’s fair to say that there is moral anxiety about abortion.

I think there is a reason why Hillary Clinton called it “a sad, even tragic choice to many, many women;” why President Obama expressed his belief in The Audacity of Hope that “few women made the decision to terminate a pregnancy casually; that any woman felt the full force of the moral issues involved and wrestled with her conscience when making that heart-wrenching decision.”

On a more personal, less political level, Jennifer Senior documented this anxiety in a story she wrote for New York magazine, “The Abortion Distortion.” Senior visited the Allegheny Reproductive Health Center in Pittsburgh, and spoke with counselor (and former director) Claire Keyes:

Keyes knows that most women refer to the developing lives inside of them as ‘babies,’ rather than fetuses, whether they’re conflicted about their abortions or not. She knows that occasionally women want to keep sonograms of the fetuses they’ve aborted and even ask to see their reassembled remains once the procedure’s through. (This is standard medical procedure, in order to make sure all the parts have been removed.) While many of her clinic patients are at peace with their decision, others are not, and she’s got piles of loose-leaf binders containing pink hearts inscribed with messages to husbands, boyfriends, parents, God (‘A lot are to God’), and the never-born that express those feelings of uncertainty-like this one, written in the bubble handwriting of a teen who had accompanied her friend: To the unborn child, Know that your mom made the choice to keep you in heaven and this was not easy for us. (I was her support.) At the end of each counseling session, Keyes offers women a basket of stones from which to choose and make a wish. In early 2008, she built a small sanctuary in her clinic so that women and their partners could ‘say a final good-bye or a prayer, or just to sit quietly and not think anything at all.’

I think abortion is “heart-wrenching” because something dies in an abortion-something that, ordinarily, would eventually grow into what everybody agrees is a human person. Some people think this “something” is a human person from the moment of conception. Others think it is a human person only after it leaves its mother’s body. Many others fall somewhere in between, and believe that abortion should be legal, but restricted in this or that way.

Why do they fall somewhere in between? I don’t think it’s absurd to suggest that it’s because they’re uncertain. Yes, they affirm a woman’s right to choose whether or not to carry her pregnancy to term. But… something dies, something that, ten weeks into the pregnancy, has hands and a face. They’re uncertain about just what that something is. And from that uncertainty arises moral anxiety: if the fetus is not a person, then we need not worry overmuch about disposing of it. But if the fetus is a person, then abortion is a moral horror.

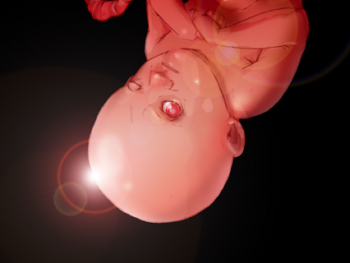

My comic series Alphonse takes that horror-that notion that hovers over many facets of the debate-and makes it overt. It imagines a fetus whose personhood is so manifest that he has the faculties of a fully developed adult. A fetus who is consumed with rage after suffering betrayal at the most fundamental level, and who vows revenge on those who sought to take his life. Alphonse is literally a monster-”a fetus or an infant that is grotesquely abnormal and usually not viable”-one I hope bears some of the perversely prophetic character of the freaks who populate Flannery O’Connor’s short stories. (Think of the Misfit in “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” or the club-footed boy in “The Lame Shall Enter First.”) He is my attempt at what O’Connor would call a “large and startling figure,” whose grotesque character upsets the ordinary way of the world.

And like the Misfit, he is not the center of the story, not really. Everybody remembers Hannibal Lecter from The Silence of the Lambs, but of course, the story is really about a damaged young woman’s attempt to silence the demons that have haunted her from youth. (“Have the lambs stopped screaming, Clarice?”) So yeah, Alphonse is the monster who makes the cover, but Alphonse is very much the story of eight lives that intersect after an attempted abortion. It is not a polemic, not a treatise, not a piece of propaganda. It is, I hope, a good horror story.

* * *

As I said, that’s the rationale I wish I could give. But even though I think all of the above is true, it’s also hindsight. It’s not where Alphonse came from. I didn’t sit down and wonder, “How can I best explore the moral anxiety surrounding abortion in a fictional setting?” That’s not how inspiration works-not for me, at least.

It started with Pixy, a 1993 graphic novel by Max Andersson. From the promo copy:

Alka Seltzer and Angina Pectoris have all the luck — bad, that is. They’ve been ejected into the street because their apartment was put to sleep, Angina had to abort their child (the result of a malfunctioning Safe-Sex bodysuit) — how could it get worse? When a friendly stranger offers them his apartment, things seem to be looking up… but then Angina gets a call from the Netherworld. It’s her aborted fetus: he’s drunk and he’s pissed off. So begins Pixy, which Neil Gaiman calls ‘the best comic I’ve read this year.’

Me, I never got past that devastating phone call from the Netherworld. I closed the book and put it back on the shelf at the comic shop. But the image stayed with me.

That was the beginning. And I confess to feeling a serious twinge when I watched Kill Bill Vol. 2 and saw the Bride instantly transformed by the realization that she was pregnant. “Before that strip turned blue, I was a killer who killed for you. But once that strip turned blue, I could no longer do any of those things. Not any more. Because I was going to be a mother.” (I don’t know if it’s permissible to have earnest emotional responses during Tarantino’s movies. Can’t help it.)

But things really took off with Umbert. (File under: you don’t always get to choose your muse.) Longtime readers of Gawker may recall the site’s mention of a comic strip character called Umbert the Unborn. Umbert is a fetus in utero who is endowed with reason, will and detailed knowledge of the world outside the womb-including legalized abortion. Umbert is clearly intended to be sweet and endearing (and too adorable to abort), but he got me to thinking-what if it were true? What if there was a fetus who really was sentient, who was suspended upside down in the dark, and who knew he was slated for termination? What would that do to a person? I figured it would leave him deeply twisted-consumed by fear and rage, but also desperate for love. That’s Alphonse.

I first wrote about my inverse-Umbert in a memoir I had pitched and sold to a small Catholic press. They were so unhappy with the finished manuscript that I ended up having to return my advance; the letter my editor wrote me explaining where I had gone wrong mentioned Alphonse in two separate places. (And my editor was pro-life.)

But my little monster stayed with me. I made one sketch, then another. And then, all at once, the first page of a comic. I am not much of an artist, but I hung on to that page. Eventually, I wrote a script for that opening scene. And then for the whole story. Long story short: three years after that first sketch, and after pitching everyone I knew in the comic and book publishing worlds, I decided to self-publish. (Just like Bone! Except, you know, without the charm and probably the genius.) I begged enough money from friends and relatives to hire an artist and letterer for my first issue. When I learned about the micro-financing site Kickstarter.com, I used it to beg enough money for issue two. These days, I’m begging again.

* * *

Why did Alphonse stay with me? Well, the easy answer is because of my parents’ patient and tireless efforts on behalf of the unborn. And while my own involvement does not really compare to theirs, I am still squarely in the camp that holds to the personhood of the fetus from the get-go. I remain convinced that abortion matters, and matters enough to make a quixotic project like Alphonse-which runs the risk of offending people on both sides of the issue-worthwhile.

But there is another reason-less why Alphonse has stayed with me, more why I have stayed with Alphonse. Last Saturday afternoon, my 12-year-old son was sitting on the living room couch, reading a magazine put out by a pro-life organization. I was at the dining room table.

“Dad,” he called to me, “Can you give me some pro-choice literature?”

“Yes, I can,” I said. “Why do you ask?”

He held up the magazine. “I want them to read this. And it would be hypocritical of me to ask them to read it if I didn’t read their stuff.”

I was proud of him. I did not introduce my son to the abortion issue, but once he came to me about it, I tried hard to get him to consider the opposition before making pronouncements. That kind of consideration is not easy when you are 12 and you believe that abortion ends a human life, but here he was, making the effort.

I don’t imagine that Alphonse is going to change anyone’s mind about abortion, and that’s okay. That’s not why I wrote it. Rather, I was trying to make a work of art (however minor) that would do some of the things that art does-reflect experience, engage imagination, and just maybe, enlarge perspective.

Matthew Lickona is a staff writer for the San Diego Reader, a weekly newspaper. Alphonse can be purchased online. The first issue is available as a PDF here.