Church: Prologue, "This Is a Song"

by Dan Kois

On a Sunday last fall, I was working downstairs with the space heater on and the office doors closed when the phone rang. The caller ID read DAN KOIS, which meant that it was my wife, upstairs, calling our home phone from my cell phone. As is often the case on weekends, we were trading carefully-negotiated Work Periods. I was writing while she looked after the children; later, I would take the kids while she worked. Later still, we would maybe eat dinner together and then put the kids in the bath.

I answered the phone. In the background I could hear crying. Alia said, “You have to come upstairs right now.”

“Okay, I’ll be right there,” I said.

“I am not facing this alone,” she said.

“Okay,” I said.

In the dining room, our four-year-old, L., was sobbing.

“I don’t want to die!” she wailed.

Her sister H. was standing next to her, wearing a two-year-old’s idea of a concerned look, and patting her arm. “She’s crying,” she told me. Her job done, she tucked a sippy cup under her arm and wandered off to the living room.

“What happened?!” I asked.

“I don’t want to ever die!”

“Oh, honey,” I said, kneeling down next to her. “It’s not something you’ll have to worry about for so long! Not until you’re very, very old.” I could feel the heat from her cheeks. She wasn’t calming down. I didn’t know what to do. Why was she freaking out about dying? She is four! What could I say? I didn’t want to lie to her, but I realized immediately that I absolutely would lie to her if necessary.

“It’s something that happens to…” I stopped myself, hearing her questions spinning out from there: Will Kiki die? Will Mommy die? When will Mommy die? So many conversations with L. get derailed by us not thinking three steps ahead. “It’s not, you don’t — “

She interrupted me, thank goodness. “Where will I go?” she asked.

“Well,” Alia hazarded, “We don’t know exactly what happens when you die.”

“Why we don’t know what happens?”

“No one’s ever told us,” I said. “It’s a mystery. Some people think you just go to sleep and never wake up.”

“I don’t want to sleep and not wake up!”

I picked her up. She was bereft, betrayed. Her anger-hey, this was never part of our deal-was only exceeded by her panic. It was horrible.

Alia stepped in. “Well, some people believe that when you die you go to a wonderful place with all your family and friends.”

“What’s the wonderful place?” Other than a grandparent-instigated christening, our kids had never been inside a church.

“It’s called Heaven,” Alia said.

“Or, or,” I said, grasping, trying to head off her next question (“Why are my family and friends in Heaven?”) before it came. “Some people think that after you die you come back to earth as something else.”

“Like what?” she said, muffled, her face pressed against me. A glimmer of interest.

“Like a, like a ladybug — “

“I don’t want to be a ladybug!”

“Or a giraffe! Or an elephant! What if you came back as an elephant? Wouldn’t that be crazy?”

I felt her smile into my shoulder. “Or a monkey,” she said.

“That would be crazy too.”

“Ooh ooh, aah aah,” her sister said from the other room, helpfully imitating a monkey.

She straightened up in my arms and looked me square in the face. “Wouldn’t it be funny if I died and I came back as an elephant?” she asked.

Oh yes, I thought, looking into her eyes. Wouldn’t that be funny. I have had nightmares about something happening to you, kid, and in the nightmares the logical next step is to just fucking kill myself. When I wake up from these nightmares, the realization that you’re not dead makes me weep with gratitude, my fat awful tears dampening the pillow.

“Yeah,” I made myself say. She put her head back on my shoulder. My eyes met Alia’s. “If you died and came back as an elephant, it would be really funny.”

* * *

Later that night I turned down the lights in L.’s room to the level, somewhere just below full daylight, at which she will agree to sleep. She was scrubbed and washed and brushed and wearing new pajamas as she padded around, putting her babies to bed, each doll with its own blanket and pillow. “This baby wants a baby doll to sleep with,” she told me, and tucked a small action figure of Space Jam-era Michael Jordan under the doll’s arm.

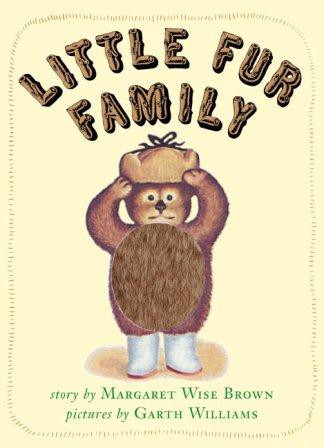

We settled down together on the floor for books and songs. She’d chosen her book, the Richard Scarry collection she loves; I chose Little Fur Family, a book I’d been reading to her a lot. Margaret Wise Brown’s story of a little fur child and his adventures in the wild wood appeals to my appreciation for the anarchic and the enigmatic in children’s stories; it doesn’t exactly make sense, but it feels right. L. plopped down next to me on the floor and draped herself over my legs. Her closeness was both endearing and irritating. “Can you move a little bit, so I can read the story?” I asked.

The little fur child caught a fish and threw it back. He caught a bug and let it loose. He caught “a little tiny tiny fur animal”-himself in miniature-and kissed its little fur nose and set it down on the grass. The little fur child returned home to his family, and his big fur parents held his hand and sang him to sleep:

Sleep, sleep, our little fur child,

Out of the windiness,

Out of the wild.

Sleep warm in your fur

All night long,

In our little fur family.

This is a song.

I took the book with me, leaving L. humming herself to sleep in her well-lit room. She hadn’t mentioned dying since the freak-out this afternoon, and we hadn’t raised it. After dinner, Alia told me it all started when they’d been discussing fairy tales, and L.-remembering the story of Sleeping Beauty, who wakes up when she is kissed-asked what would have happened if no one had ever kissed her. And from there everything spun out of control.

While in theory we want to be as honest with our kids about the world and its trials, in practice we’ve shied away from any discussion of death at all. (The week of Michael Jackson’s overdose was a week of total news-radio blackout in our car.) The larkish nonchalance with which Alia and I, and all our friends, discuss anything grave-that generationally understood shorthand that connotes, “Yes, death and terrorism are terrifying, and I take them seriously, but que sera, right?”-doesn’t signify to a four-year-old. Four-year-olds are serious. Four-year-olds do not want your ironic worldview. Four-year-olds want to know how to feel, how you feel.

I opened the book and looked at the little fur family, the father and mother singing, the little fur child snug in his bed. It feels, sometimes, as though we lack even the framework within which to talk about real life with our little fur children. They never catch fish or run through the woods. They never decide whether to let the bug loose or to squash it underfoot. All we can give them are borrowed traditions-offering other people’s theories one after the other, hoping one interests them enough to push us gently to a new topic. We talk to L. about the sort of person we want her to be, and we do our best to be those sorts of people. But her world is full of little fur families who talk and act and look and believe-or don’t believe, or can’t believe-as we do.

This is right and this is wrong, we say. This is kindness. This is a song.

Other than that christening, and a handful of weddings and christenings and Christmases, I hadn’t attended church in 16 years, since high-school Methodist Youth Fellowship. A few weekends after that day in September, we put on our Sunday clothes and drove around the corner to Rock Spring Congregational. There were other reasons we returned to church besides that terrifying conversation with L., of course. But as we walked through the big wooden doors-the greeter shaking our hands warmly and leaning down to compliment L. and H. on their dresses-I was thinking about the little fur child as he lets the tiny, tiny fur animal loose on the grass and watches it run.

Dan Kois writes about movies and plays and books, too. Also, he has a new book out, about that Hawaiian guy with the ukulele. Why not buy it?