The End of the 00s: How To Lose Your Idealism In Under Ten Years, by Natasha Vargas-Cooper

by The End of the 00s

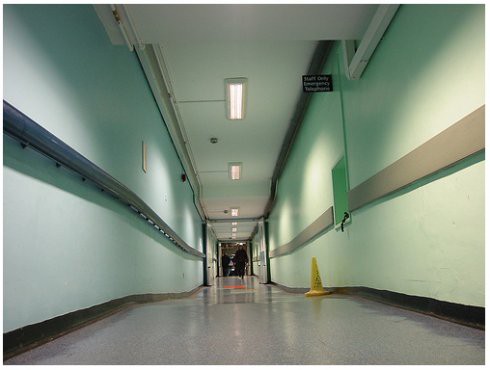

Blanca, a 50-something nursing assistant, was sitting across from me at the nurses’ station at the Intensive Care Unit inside of a Tenet Healthcare Corporation-owned hospital in downtown Los Angeles. It was midnight, and this was 2004. Blanca’s patients were gurgling, asleep or comatose. I was there talking to Blanca on behalf of workers at Kaiser, who were bargaining away benefits because Tenet, the for-profit, non-union hospital chain was driving down wages in the county. The argument was that every one would be better off, Blanca and Kaiser workers, if they were all in one union.

During advanced pneumonia the lungs fill with fluid so there’s a wet gurgling sound emitted during exhalation. The respirators made a swoosh-pffft noise as they breathed for people who can’t. Every thirty minutes or so there’d also be a moan; some sort of agonized cry. If the moan lasted for more than 30 seconds, its owner would be visited.

Blanca made $13.25 an hour after 12 years of being a nursing assistant. Her main issue was pension. She wanted to retire in ten years. Tenet offered no such deal. Blanca eventually became a leader in her department. She signed up her co-workers on a petition to organize, proudly wore her “union: yes” button, and put her face on a flyer with a pro-union quote. The risk of going public in support of a union in a hospital of 700 hundred employees when you’re an immigrant whose job it is to wipe asses from 7pm to 7am should be self-evident.

The union won the election a month later by a narrow margin. Blanca and her co-workers got a solid contract, complete with 401k plans and 14% percent wage hike.

Four years later, Blanca and her co-workers would be picketing outside my office at the union’s headquarters in Washington D.C.

It was an extremely ugly fight. It went on for more than a year. It was essentially was a war over who had jurisdiction to organize sectors of the healthcare market, between the local union chapter and the international union. It was turf war cloaked in the language of ideology, union democracy, progressive organizing and political purity. Any one with the smallest sense of organizational acumen could see it for what it was: a naked power struggle between two union bosses that employed the rank and file to carry out their competing agendas.

So, there’s Blanca’s and other union members holding picket signs, chanting ‘SHAME ON YOU’ at anyone who crossed the picket line. I crossed without a second thought. By 2008 I shrugged at any symbolism that act held; I was completely disillusioned and numb and just wanted to get to my WiFi connection.

* * *

My disillusionment was not inevitable. It’s not a story about a boundless idealism that could only rot when exposed to the mendacity of ‘real politics.’ Actually I’m a pragmatist to my core: I was well aware that I was part of an imperfect institution that was trying to solve a very big problem. 91% of the American workforce did not have the right to collectively bargain their wages, job security or retirement. My belief was that I could have a fulfilling career by trying to fix this problem. I knew that any bureaucracy or institution would be clogged with deadwood, indolence and dysfunction. But I also knew there those who were capable of transformational leadership.

The problem was that most of the decision makers-whose salaries were funded by the 1.2 million dues-paying members-were made up of baby boomers. And today, I can tell you that I will never work for an institution that is lead by that generation, never again.

* * *

Those who make a career of professional do-gooding, do so because it fulfills some psychological need; altruism, guilt, vanity, ego. Obviously, there is no problem with that. Whatever motivates someone to get into public service, or any profession, is immaterial when compared to their accomplishments.

But the psychological needs of the Boomer generation are not something I can suffer.

And suffering is a big part of it. Their ideological hangups are infecting every aspect of life. As they age, they are only getting worse.

Politically, their numbers and self-regard are basically the reason why our ‘idealistic’ generation is disenfranchised by the political process. The left has ceased to be an agent of social change for the past forty years; the right is cannibalizing itself. The political battles between the two have, as the battle has gone on, become symbolic, rather than being about actual, tangible benefits for real-life people.

This is not a fight worth my time. I don’t plan to squeeze any humans from my womb. What problems and solutions exists now are the only ones I will ever know.

Culturally, I find the Boomers tedious and unhelpful. Their confused notions about counterculture have infected our generation. The kind of water bottles you buy, car you drive, fair trade coffee you slurp: can this serve as some kind of political action? This idea is laughable. It gives the false illusion of social engagement. It leads us to the conclusion that you fight the structural problems of capitalism by buying non-mainstream things: like leggings or a Prius! But capitalism loves counterculture. It thrives on it! Just flip on your TV at 3 a.m. and watch Peter Fonda hawk the TIME LIFE GOLDEN 60S music collection!

Economically, the Boomers have devastated the country. We inherited debt, a shredded safety net; pensions went the way of the horse and buggy; largely, no one born after 1982 will ever have a full-time job. I don’t know what the new economic model is. We are a waning empire that has seen unparalleled progress and expansion in the modern era. That’s unraveled.

This was the same critique that was leveled at the stultifying Eisenhower generation by the Boomers. Maybe my disappointment is just a product of being young. Or maybe the Boomers were right then and they are wrong now.

* * *

Mine is, I suppose, a transitional generation. Things may get worse; they may get better. I don’t have any interest in butting against the structures of the previous generation any longer.

My father, Marc, told me a story about his anarcho-syndicalist reading group in college. Their leader was Farhar, a British-educated Iranian who loved to wear silk scarves and crushed velvet blazers. He was from money, his speeches were entrancing, and he loved Marx. One day my dad and his dirty finger-nailed crew asked Farhar why he traipsed around campus dressed like a Victorian aristocrat? Why, if he believed in the power of the proletariat, did he live his life like an elite? Farhar expelled a plume of cigarette smoke and said, “Marc, just because I know the workers will take over the means of production doesn’t mean I have to join them.”

Best of luck, tweens.

Natasha Vargas-Cooper works for herself now.